Russia won’t stop its aggression. NATO-backed Ukraine won’t cease its counter-offensive. The threat of nuclear conflict is growing. Unspeakable brutalities are discovered every day. Everybody wants to curse the darkness. But there is one candle of hope.

If good speeches at the UN—which fill the air this week at the United Nations General Assembly’s annual debate—could save the world, we’d all be in bliss. Unfortunately, good speeches can’t stop the Ukraine war, which has now reached a point of maximum danger for humanity. Russia won’t stop its aggression. NATO-backed Ukraine won’t cease its counter-offensive. The threat of nuclear conflict is growing. Unspeakable brutalities are discovered every day. Everybody wants to curse the darkness. But there is one candle of hope.

Right now, the major powers in the UN Security Council are running over the UN, cynically disregarding their legal obligations to maintain international peace and security. They consider the UN useful in providing humanitarian aid to the victims of conflicts, but have stripped it of its enforcement powers to stop wars.

The institutional breakdown of the UN Security Council, caused by the five permanent members, who selfishly put their own interests ahead of the good of humanity, is a chief reason for the disrespect all institutions are enduring today. The crisis of disrespect for law the world over has led to the present doleful situation in which politicians merely wring their hands at the senseless war started by Russia.

Guterres can’t haul the big powers into court. But he can look into the near future and identify ways to strengthen crisis management and build the conditions for peace. That’s what his “New Agenda for Peace” will address.

This is not the first time such an agenda has been attempted at the UN. In 1992, in the immediate aftermath of the Cold War, the UN secretary general at the time, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, published “An Agenda for Peace,” which listed measures for conflict prevention. Boutros-Ghali wanted a $50-million peacekeeping reserve fund, a $50-million humanitarian revolving fund for emergency assistance, and a $1 billion peace endowment fund. He wanted to pay for this through a levy on arms sales and a tax on international air travel (which is dependent on the maintenance of peace). Apparently, he reached too far, for his proposals were sidelined. Some of his ideas, however, gradually found their way into UN peace-building initiatives.

Now, three decades later, the world is truly frightened by the consequences of the latest eruption of war. “I think we are all concerned that if [Putin] is pushed to the edge, he might respond in what you would consider a horrific way, making use of a weapon of mass destruction,” Rose Gottemoeller, NATO‘s former deputy secretary-general, not known as an alarmist, said. Even China’s leader Xi Jinping and India’s prime minister Narenda Modi have signalled their concern at escalating warfare.

But is this concern deep enough to move world leaders to support Guterres’ efforts to develop a new agenda with any teeth in it? The General Assembly is currently considering how far the new document can go beyond merely setting out benchmarks to measure the risks of inter-state warfare. The International Crisis Group, an independent civil society organization working to prevent war, wants Guterres to adopt a broad definition of “strategic risks,” which would not only reduce the nuclear danger but also address the sources of instability in the Global South, such as the proliferation of small arms, inequality, global warming, and the challenges poorer states face in delivering basic services to their citizens.

This is precisely the moment to advance the concept of common security—the idea that nations and populations can only feel safe when their counterparts feel safe. This was first proposed during the Cold war by an international commission headed by Olof Palme, a former Swedish prime minister, who insisted, “International Security must rest on a commitment to joint survival rather than a threat of mutual destruction.” This is not as easy as it sounds.

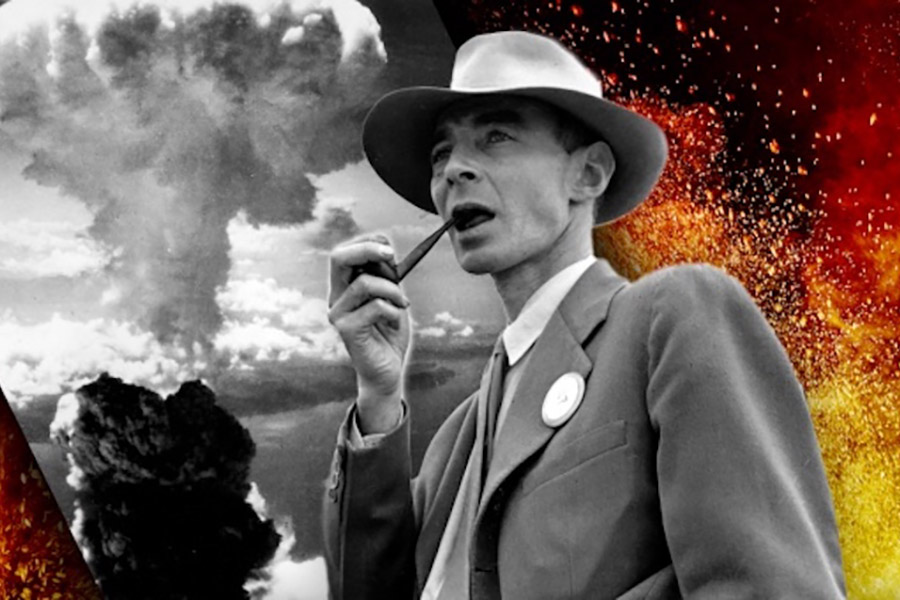

Common security counters the military doctrine of nuclear deterrence, which all the permanent members of the UN Security Council live by. Nuclear deterrence is responsible for the continued nuclear arms race, the source of so much tension in the world. If the major countries were really serious about building peace, they would negotiate away their nuclear arsenals. They won’t do this, as the recent Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference showed.

Thus Guterres is stymied. He can go only so far in projecting his new agenda. I think he should aim for the support of the middle power countries in challenging the major states’ war policies.

Here Canada has a special role to play in backing Guterres’ efforts. Right now, we’re following NATO’s insistence on Western military dominance. That is not the route to common security. Canada needs to give more support to the UN’s New Agenda for Peace rather than adhering so closely to NATO’s plans to keep fighting the Ukraine war. We need to build hope for peace through new thinking.

Former Senator, the Hon. Roche, O.C., is on the Board of Advisors of the Global Security Institute. He is an author, parliamentarian and diplomat, who has specialized throughout his 40-year public career in peace and human security issues. He lectures widely on peace and nuclear disarmament themes. Mr. Roche was a Senator, Member of Parliament, Canadian Ambassador for Disarmament, and Visiting Professor at the University of Alberta. He was elected Chairman of the United Nations Disarmament Committee at the 43rd General Assembly in 1988.