The death of Alexei Navalny in one of Vladmir Putin’s terrible prison camps in the Arctic Circle is a tragedy for the world. It is also a marker and a reminder of the competing political forces of our time.

When the Cold War ended, democracy was on the rise, leading to optimistic visions of “the end of history” and a “unipolar moment” in which the United States and the West would further shape a liberal internationalist global system to serve the growth of democracy and global peace and order. However unrealistic these visions were, today one can easily argue that authoritarianism and illiberalism are on the rise, and liberal democracy is on the defensive. Navalny’s death, in the midst of a war in Ukraine that openly and directly challenges the global order established after World War II, and which seems likely to define a turning point in history (in what direction it will turn is unclear), further clarifies the challenge that lies ahead, and the choices to be made.

While he was in prison, Navalny exchanged letters with Natan Sharansky, the Soviet-era refusenik and reformer. Sharansky and his co-author Carl Gershmann wrote in the New York Times, shortly after Navalny’s death, “In the long line of people who have been victims of the Soviet and Russian dictators, Alexei Navalny was extraordinary. He dedicated himself to unmasking the cynical, corrupt nature of Putin’s dictatorship. And he succeeded, releasing the truth to the world.” Navalny saw his role in this light, saying in his letters that the “virus of freedom” could never be eradicated and that hundreds of thousands of people will continue the fight against Putin and tyranny in Russia.

After Navalny died, Serge Schmemann of the New York Times wrote an article entitled “In Death, Navalny is Even More Dangerous to Putin’s Lies,” In the article he characterized Navalny’s opposition to and hatred of Vladmir Putin for lying about everything, for massive corruption, for criminalizing society, and for distorting the truth about everything – especially democracy. Those who opposed Putin were labeled a “foreign agent” or engaged in “terrorism.” By contrast, Putin’s colleagues, the oligarchs, were gifted the Russian people’s assets and were made into, using Putin’s own term, “appointed billionaires.” What made Navalny so dangerous is that he broke through Putin’s lies. He never stopped pointing out Putin’s falsehoods and crimes, and he never stopped fighting. “He was a crusader,” Schmemann writes, “against corruption, against evil, against venality, and always against Mr. Putin.”

Schmemann also discussed an interview Navalny gave to Boris Akunin, a Russian writer who now lives in Britain and has been convicted of “justifying terrorism” by a corrupt court in Putin’s Russia. In that interview, when asked “What is the greatest source of evil?” Nalvany responded with the well-known quote attributed to Edmund Burke, saying “All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is the inaction of good people.” As Schmemann noted, “this was his credo, the impossibility of standing to the side while evil ran rampant.” Because of this, Navalny was not afraid to suffer, and he remained an optimist, telling Mr. Akunin, “I believe that Russia will be happy and free. And I do not believe in death.” Such words, saying that freedom will come to Russia and that the fight for freedom cannot be killed, are dangerous words in today’s Russia, as Russians at all levels understand this. It is not just a credo. It is a guiding beacon for life that should be forever remembered.

Alexei Navalny and Vladmir Putin exemplify competing currents in Russia and its history. It is a vast land with a rich and diverse culture. It has been blessed with brilliant scientists, glorious artists – writers, composers, performers, painters – and dedicated heroes struggling on behalf of the Russian people, such as Tolstoy, Kerensky, Solzhenitsyn, Sakharov, and Nemstov. Navalny is the latest of these figures. The country has also been darkened by many evil and tyrannical leaders, against whom these heroes struggled.

This goes back to Ivan the Terrible, the first Tsar and the first absolute ruler of Russia. With the title from a very young age as the Grand Prince of Moscow and all Russia, he was crowned Tsar of All the Russias and given actual power to rule in 1547 at the age of sixteen. Initially, he was a relatively moderate ruler with an advisory council that helped him institute legal reforms, an early parliament, and new practices governing the rights and activities of the aristocratic class (the Boyars). This is not to suggest a lack of violence in his rule. There was plenty of this too, and Ivan’s armies enjoyed success defeating the Khanates of Kazan and Astrakhan, greatly expanding Russia to the Urals in the East and toward the Caspian Sea in the South. However, later in life – after unsuccessful wars, a brief abdication from the throne, and particularly the death of his wife by a poisoning Ivan blamed on the Boyars – Ivan’s rule changed and came to exemplify the worst attributes of Russian autocracy. He persecuted the Boyars and confiscated many of their land holdings to give to his supporters. He established a military/secret police force called the Oprichniki (dressed in black and riding black horses) that was loyal to him to carry out his decisions, torture and kill his opponents, and enforce what became Ivan’s absolute rule and reign of terror that could not be questioned. He ordered the destruction of Novgorod, one of the most prosperous Russian cities at that time, suspecting that the nobles wanted to leave Russia and join the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. And according to one story, Ivan ordered that the architect of Saint Basil’s Cathedral be blinded because Ivan didn’t ever want him to build anything else so beautiful. This is probably a myth, but it demonstrates how Ivan was regarded.

After Ivan died, the Romanov dynasty ruled the country until the Russian revolution in 1917, and in many ways, Ivan set the pattern of governance. He established precedents and practices that many other Russian rulers (with a few exceptions) have emulated for almost 500 years, up to the present day: absolute power, terror and cruelty, a secret police to back up the ruler and put down resistance, and military conquest across the Eurasian continent.

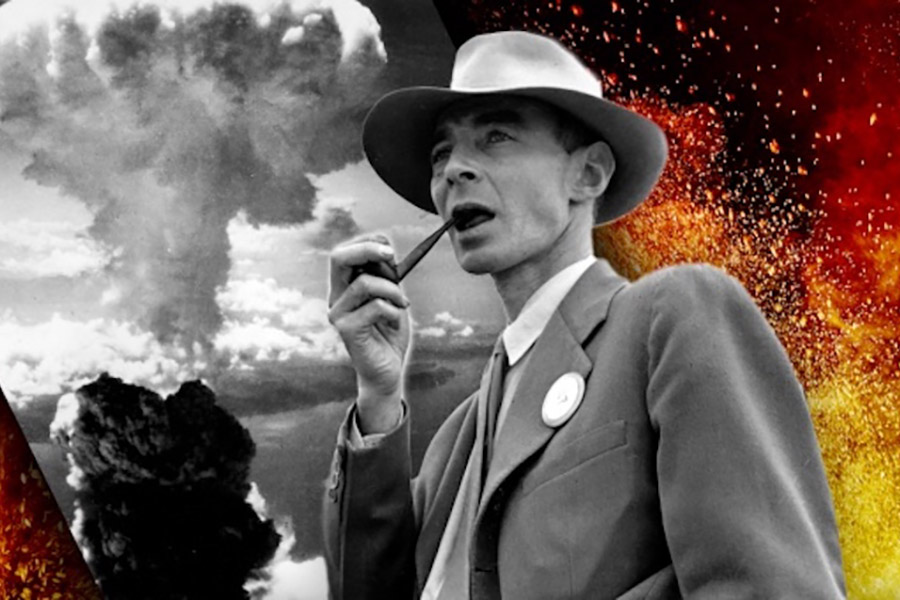

The most violent, bloodthirsty and tyrannical of all in this line of Russian autocrats was Joseph Stalin. He can be considered in this regard as a direct descendant of the worst elements of Ivan the Terrible. Responsible for the murder, starvation, and imprisonment of millions, he looked upon his mass murder campaigns as necessary to make Russia modern and strong, and to cement his hold over the Soviet Union, eliminating anyone who could remotely be considered a rival, a threat, suspicious, or tainted by contact with enemies. Timothy Snyder wrote in his book Bloodlands, “In the name of defending and modernizing the Soviet Union, Stalin oversaw the starvation of millions and the shooting of three-quarters of a million people in the 1930s [not to mention during World War II]. Stalin killed his own citizens no less efficiently than Hitler killed the citizens of other countries. Of the fourteen million people [unarmed civilians] deliberately murdered by these two regimes between 1930 and 1945, a third belong to the Soviet account.”

While Vladmir Putin is less steeped in the blood of his own countrymen, Stalin’s views of government and power do not seem to be too far off from what Putin has chosen to carry out in Russia, (also now in Ukraine and likely more of Europe if he could). Navalny and other Russian resisters and reformers have had to contend with forces that must have seemed intractable, if not impossible to overcome. They had not only the absolute monarch or dictator in their own times to struggle against, but also many centuries of political practice that has supported the concept of absolute rule with little room for dissent. It is this legacy of absolutism and tyranny – a sad, horrifying legacy of governance for Russia – that today’s heroes and reformers have to fight against.

Navalny expressed his hope that his successors could bring to an end to Putin’s regime, and the long tradition of autocracy in Russia, so that honesty, fairness, democracy and “the virus of freedom” could someday prevail. One of those who carries on the struggle is Vladimir Kara-Murza, who is currently serving a lengthy term in one of Putin’s “Special Regime” prison camps in Siberia for speaking out against the war in Ukraine. He was poisoned twice by Putin’s security forces in 2015 and 2017 and is still suffering from serious aftereffects. He fights the same fight as Navalny, and he not only sees parallels with the Stalin era, but a Russia that is increasingly moving in that direction, saying that, “There is no question that the Kremlin’s campaign of political repression is intensifying.”

Navalny and Kara-Murza, along with other brave women and men who came before them and will come after them, represent the fierce determination to do whatever it takes to see freedom and democracy prevail, to ensure that the horrors of Stalin never ever return to Russia or anywhere else, and to oppose the rise of strongmen who have undermined liberal democracy in countries such as Hungary, Brazil, India, and even the United States (Putin is the genuine article, but he has plenty of friends, admirers, and would-be imitators around the world). All of us have a part to play in this drama, and it is important to lend our full support to those in the first line of freedom fighters, particularly in Russia and Ukraine, where the cause is so urgent. A successful outcome in this struggle must be won so that not only Russia, but countries everywhere, will be happy and free.

Following the example of Alexei Navalny, who has set an inspiring example for people everywhere, we are optimistic about this outcome. We may have no proof, but we have no doubt.

This story originally appeared at Democracy Paradox

Ambassador Graham served as a senior U.S. diplomat involved in the negotiation of every major international arms control and non-proliferation agreement for the past 30 years, including The Strategic Arms Limitations Talks (SALT) Treaties, The Strategic Arms Reduction Talks (START) Treaties, The Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty, Intermediate Nuclear Force (INF) Treaty, Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty, and Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT).

David Bernell is an Associate Professor of Political Science in the School of Public Policy at Oregon State University. His research and teaching focus on international relations, American domestic and foreign policy, and US energy policy. He is the author of the books Constructing US Foreign Policy: The Curious Case of Cuba, and The Energy Security Dilemma: US Policy and Practice. Prior to coming to OSU, he served as an appointee in the Clinton Administration with the US Office of Management and Budget, and with the US Department of the Interior.