By Jonathan Granoff and Garry Jacobs

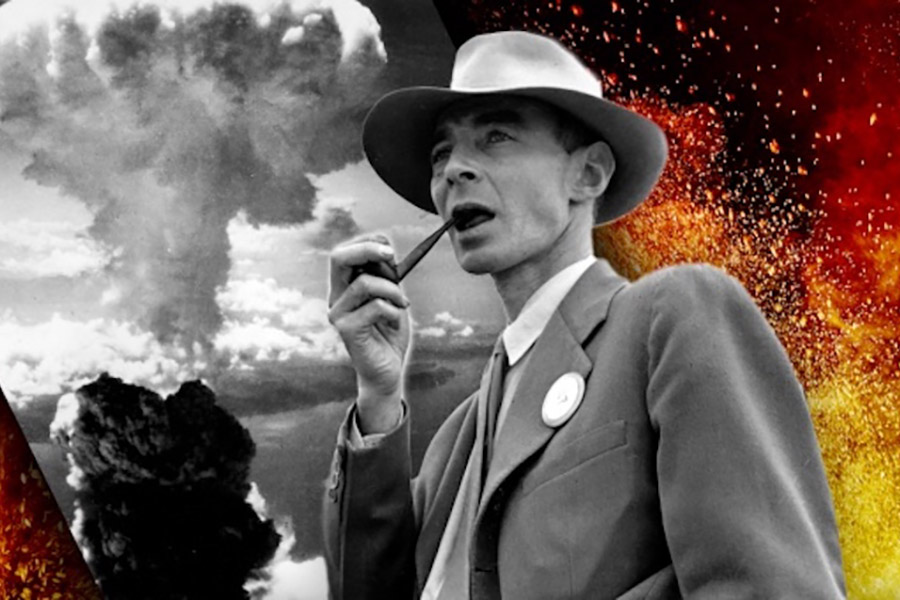

The Oppenheimer movie has attracted global attention and the highest film awards. It tells a gripping story of unprecedented global events that changed the course of history, unleashing a veritable Pandora’s box that continues to haunt humanity eight decades later.

The film is factual, and in many respects true to life, but it does not tell the whole story or reveal the full significance of the events it depicts, which are as relevant today as they were at the time the events unfolded.

The Industrial Revolution was driven by successive stages of technological innovation that powered the transition from manual labor to steam and electricity during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Modern science can trace its origins back to the onset of the Age of Enlightenment in the 17th century, but until then it remained in a virtual ivory tower of academic detachment, pursing knowledge for its own sake with relatively modest impact on the daily lives of human beings and the destiny of nations.

It was only during World War II that science emerged as a power to shape the future destiny of nations, humanity and our planet. As Albert Einstein stated it so succinctly, “The unleashed power of the atom has changed everything except our way of thinking. Thus, we are drifting toward catastrophe beyond conception.” [1]

This change in “everything” is the central focus, as grippingly depicted in Oppenheimer. The detonation of the first atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki changed the world almost overnight.

Science as a formidable source of power

For the first time, science became recognized as a formidable source of power to be reckoned with–greater even than the most powerful armies and wealthy economies.

From then on, scientists could no longer assume a detached position aloof from the destiny of nations. Their knowledge and powers for invention were too great to be ignored or denied.

Oppenheimer, Neils Bohr and other scientists involved in the Manhattan Project believed they were applying their knowledge to save the world from devastation by Germany. Once Germany surrendered, they saw no need to use the bomb and strived to persuade President Truman to abandon the plan.

They also warned him that sooner or later, Russia and other nations would acquire the same power and unleash a global race for nuclear supremacy.

After Hiroshima, their continued efforts to promote a global ban on the use of nuclear energy for military purposes were largely ignored, though it did lead eventually to the establishment of the International Atomic Energy Agency years later.

The film Oppenheimer overlooks one of modernity’s great heroes, Dr. Joseph Rotblat, with whom Oppenheimer joined in voicing the need for moral and legal restraints on the power that modern science had bestowed. Rotblat walked off the Manhattan Project when it was clear that the Nazis could not build an atomic bomb because the British had destroyed the “heavy water” facility in Norway that Germany needed.

He told General Groves, the military leader of the Manhattan project, of this fact but discovered that the bomb was being built, not just to deter the Nazis but also to challenge the power of the Soviet Union. Rotblat saw the danger of an arms race if the US built and used the device.

History proved that his fears were fully justified. By the early 1950s, Russia and America were engaged in a nuclear arms race that eventually gave rise to more than 70,000 nuclear warheads – enough to destroy humanity and the earth’s environment many times over.

Profound impact

The onset of the Cold War and the nuclear arms race had a profound impact on the position of science in global society. It also led to profound reflection among scientists and a gradual change in the attitude of the scientific community regarding their role in society and responsibility for the consequences of their discoveries.

This culminated in the release of the famous Russell-Einstein Manifesto in 1955 through which Albert Einstein and Bertrand Russell, along with nine other distinguished scientists, alerted the world to the growing dangers of the nuclear arms race.

The Manifesto closed with this admonition: “We appeal as human beings to human beings: Remember your humanity, and forget the rest. If you can do so, the way lies open to a new Paradise; if you cannot, there lies before you the risk of universal death.”

A year later, the First International Conference on Science and Human Welfare was convened in Washington, D.C., to focus on the social responsibility of science and scientists. The conference called for establishment of a World Academy of Art & Science (WAAS).

Two years later, Polish mathematician Jacob Bronowski published Science and Human Values as a statement and reflection of the increasing recognition that scientists could no longer remain detached bystanders in quest of truth for truth’s sake.

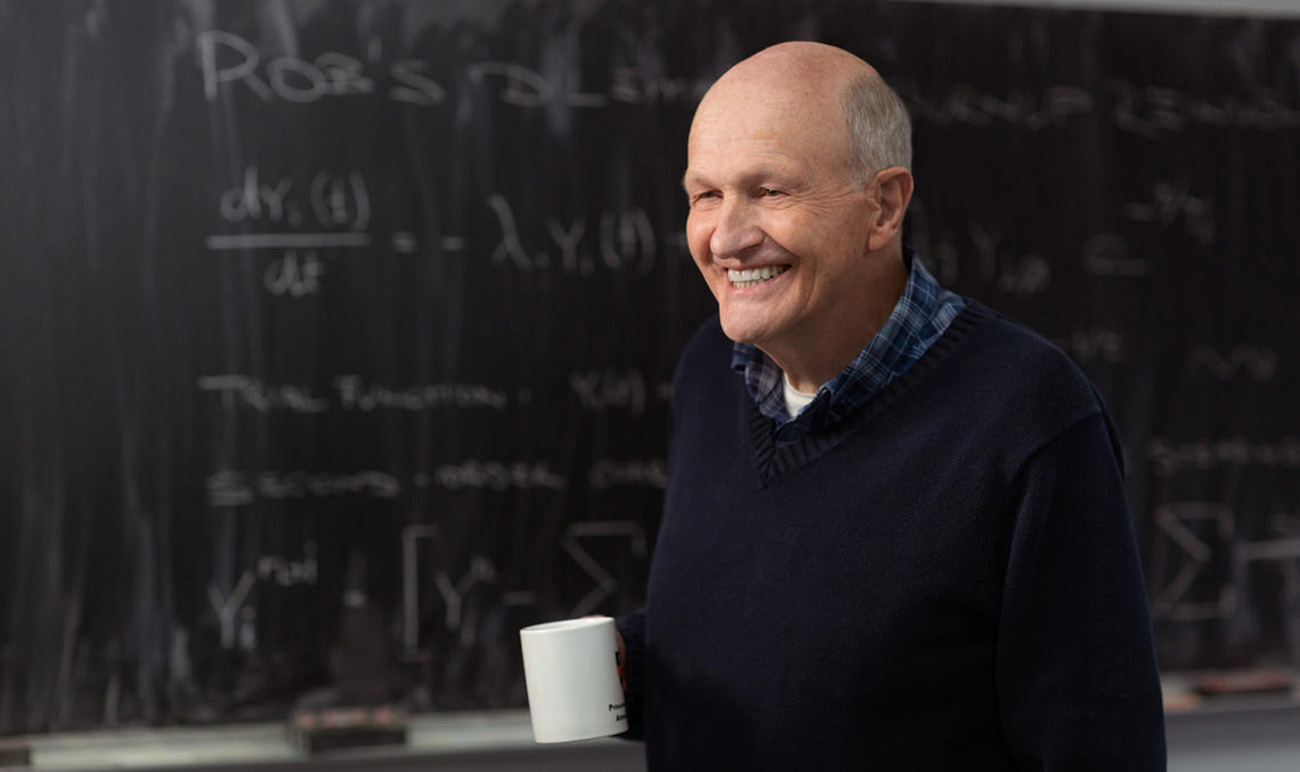

WAAS was officially founded in Geneva in 1960 with about 50 founding members, which gradually grew to 100 and today has more than 800 eminent intellectuals from more than 80 nations drawn from the natural and social sciences, arts and humanities, business, engineering, medicine and other professions. Dr. Robert Oppenheimer, along with Dr. Rotblat, were founding members of this inspiring endeavor.

Unlike traditional science academies, the stated objective of the Academy’s founders was not the pursuit of science itself but rather to be an “Agency for Human Welfare” — utilizing science, technology and other forms of knowledge as a means to promote the well-being and security of all human beings.

Since then, the work of the Academy has focused on a succession of pressing global challenges, such as health, population explosion, food shortages, environmental destruction, war and peace, economic and financial crises, poverty, inequality, migration, refugees and human insecurity.

In each case, WAAS has approached the subject from a transnational, non-partisan perspective, seeking solutions applicable to people and nations around the world.

Rather than fragmented disciplinary silos, it approaches problems from a human-centered, values-based, comprehensive, transdisciplinary perspective, integrating the objective perspectives of science with the subjective insights of the arts and humanities.

WAAS recently entered into a partnership with the UN Trust Fund for Human Security to launch HS4A, a Global Campaign on Human Security for All and is working to promote a new paradigm in security focused on the safety and welfare of people rather than the competitive security of nation-states.

Human Security, unlike the pursuit of military dominance and the daily threat of mutual annihilation, places the needs of people first, reminding nations that only through cooperative security, wherein global threats are addressed collectively, can any nation truly secure its own people.

It is a realistic approach that recognizes the impact of science and technology on a global scale and focuses as well on local programs that directly serve people’s needs.

A human centric approach is a practical necessity to address the next pandemic, stop climate change, protect the environment and foster the regenerative processes of nature upon which human civilization depends, such as the health of the rainforests and the oceans, which provide the very oxygen necessary for every person everywhere to live.

We need to change our perception of how security is obtained by placing emphasis on the web of life, rather than national military power. Only then will science and technology serve, as WAAS founders intended, to advance a “paradise” for humanity.

The HS4A campaign includes collaboration with a wide range of organizations such as the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU), an association of 180 national parliaments; IAP, an organization of 150 science academies; SDSN, the UN global social network of universities; and CTA, the Consumer Technology Association, an organization including the world’s leading business and technology companies, which hosts the annual CES show, among others.

Seventy-five years after the first donation of the atomic bomb, the nuclear genii is still out of the box and once again threatening the security of people around the world. And today humanity faces another existential threat to peace and security, artificial intelligence.

AI is arguably the most powerful technology ever developed by human beings. It has the potential to solve many of the most severe problems confronting humanity today. But like other technologies, it is a double-edged sword which can cut both ways–as a force for good or a force for destruction.

The challenge humanity confronts today is how to harness the unlimited creative powers of science and technology for the good of all while controlling and protecting humanity from ever-greater threats and an even increasing sense of uncertainty, insecurity and fear of what the future will bring.

As in 1945, scientists together with policy-makers will continue to play a critically important role in determining the outcome for humanity.

Today there are many dedicated leaders and organizations striving to ensure that we find ways to ensure a safer and better future for people everywhere. It is noteworthy that the scientists who birthed the atomic bomb understood the necessity of choosing the way of peace.

[1] Hypnosifl 22:42, 7 November 2011 (UTC)

This story first appeared at In Depth News (IDN) the flagship agency of the Non-profit International Press Syndicate.

Jonathan Granoff is the President of the Global Security Institute, a representative to United Nations of the World Summits of Nobel Peace Laureates, a former Adjunct Professor of International Law at Widener University School of Law, and Senior Advisor to the Committee on National Security American Bar Association International Law Section.

Garry Jacobs is President & CEO of the World Academy of Art & Science (WAAS) to which he was elected in 1995, and Executive Chairman of the HS4A Human Security for All global campaign launched this year by WAAS in collaboration with the UN Trust Fund for Human Security. He is also Chairman of the Board and CEO of the World University Consortium (WUC); President and Director of Social Science Research at The Mother’s Service Society, Pondicherry, India; Editor of Cadmus Journal on economy, education, governance and security; and Member of Club of Rome. Jacobs is an American social scientist and management consultant focusing on new paradigm concepts and strategies in the fields of business, economy, education, global governance, human rights and international security.