Remarks by Jonathan Granoff, President of the Global Security Institute

on accepting the Arthur E. Armitage Distinguished Alumni Award

Rutgers University Law School-Camden

June 11, 2009

Although it is my name and hands accepting this honor today, the reality is that any accomplishments of which I have been a part have been guided by an unseen blessed hand and the very visible guidance of several powerful teachers. It is to them that I presently want to express my gratitude.

My mother Kitty Kallen, before I was to travel to speak at a large conference in India dedicated to interfaith and intercultural understanding said, “Here is a secret. Just remember you are speaking only to one person.” My mother was a very famous singer in the 1950s and during the Big Band period. Today, while she is 88, one notices that she treats every person as that one significant person. In that way she continues to shine.

My father was a show business impresario, music publisher, television producer and the press agent for Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, and many other clients whom he helped make famous. He also demonstrated a profound sense of respect for every person. He told me not to worry about success but to pursue excellence in every activity. He said, “The cream will naturally rise to the surface.” He said, “Be direct. Gershwin was great because his melodies were simple. He did not go A to F to C but went A to B to C. Simple and direct.”

At Rutgers I learned from several outstanding professors, particularly Milner Ball and Albert Blaustein, that international20law will be necessary for local stability and security, for environmental protection, and for social justice. This was in the 1970s when I was a student here. How correct they were. Milner Ball highlighted our collective dependence on the ecosystem of the oceans and the fact that a global regime would be needed to protect it, for if one country can dump toxins in the ocean all can dump using its flag. Albert Blaustein taught me that the greatest American export is the rule of law and our greatest strength is obtained when others want to emulate us, rather than when they fear us.

My first formal teacher of moral insights was my Rabbi, Dr. Arthur Hertzberg, who rose to the highest offices in the American Jewish Congress and the World Jewish Congress. I had asked him to help me prepare an effective presentation at a UNESCO sponsored conference in Israel, where professionals from the region were gathered to discuss their role in promoting peace, lawyers, doctors, teachers, judges, psychiatrists, even dentists. After having our conference delayed and our venue changed from Gaza to the Dead Sea at the behest of Israeli intelligence warning of imminent violence from terrorists, Rabbi Hertzberg’s suggestion that I recount the story0Aof Abraham seemed more apt than I had first realized:

Abraham was asked by God to sacrifice his son, and for purposes of the point to be made, it matters not whether it be his first born, Ishmael, the Islamic narrative, or Isaac, the Jewish narrative. He accepted God’s will and was ready to obey. When he discovered that the people of Sodom and Gomorrah whom he despised as the other were at risk of annihilation for their misdeeds, instead of accepting this decree, he argued with God and challenged Him to exercise restraint based on justice. He then negotiated on behalf of these people with whom he had no personal affinity, these others, demanding that if there be ten just people that all in the cities would be saved.

When Mohamed was asked who is the most perfect in faith, he said it was Abraham. I then challenged the conference. “Cannot my Muslim brothers and sisters recognize within a people of less than 15 million surrounded by hundreds of millions threatening them, a history of thousands of years of pogroms, holocaust and general oppression, that there must surely be at least ten good people? And how can my Jewish brethren, the very children of Abraham, not see the innocence being stolen from the children of Gaza, their future filled with fear, their lives diminished by violence. Have we looked for ten just Palestinians? How long will we demonize each other? Abraham was the first human rights lawyer and he practiced in the highest of all courts.”

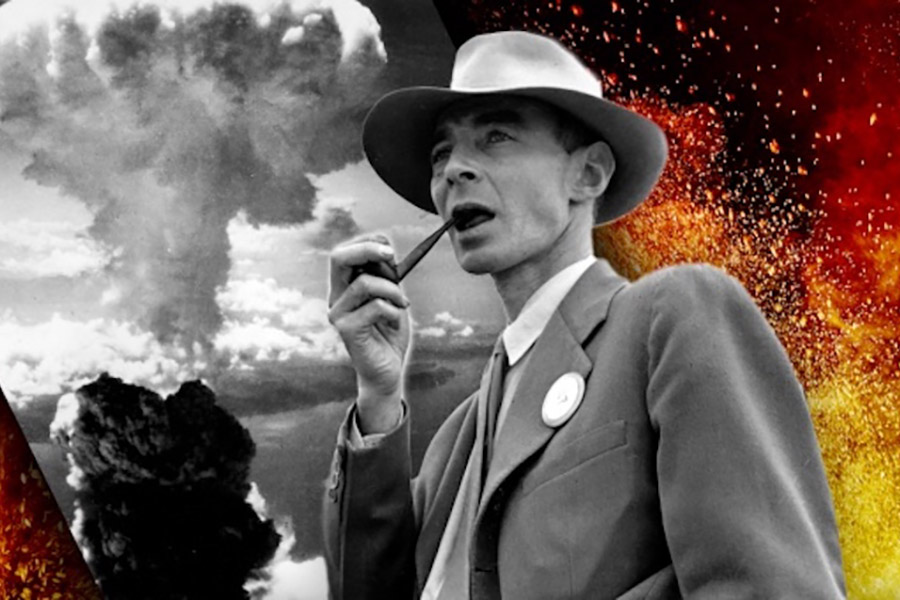

In a world awash in high tech weaponry, religious and tribal fanaticism and weapons of mass destruction, the demonization of others is intolerable. The antidote of the rule of law and the processes of diplomacy and dialogue are of critical value. During the Cold War the entire world nearly ended by virtue of two empires demonizing each other into a cul-de-sac of annihilation.

When I interned in Congress in the 1966, Senator Robert Kennedy had a meeting with a small group of us and shared lessons from the Cuban Missile Crisis from the perspective of an insider. He told us how close the world came to utter ruin and that only good luck had saved civilization. He urged us to understand that eliminating nuclear weapons before they eliminate us is the moral and practical challenge, the “litmus test,” as he called it, of our time. In the immediate years following, the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, which contains the promise of nuclear disarmament, was negotiated.

I have concluded that nuclear weapons constitute a paradox of modernity. The more the weapon is perfected the less security is obtained. It is like a horse of science and technology running without appropriate reigns of law and morality. Nuclear weapons are possessed by less than a dozen countries and are relatively easy to detect. If we cannot bring them under control through the application of a cooperative international verification and monitoring system, we should be aware that in the future our children will face new technologies of destruction where fewer people with less resources will be able to inflict greater tragedy. That is why international law is so needed today and that is one reason I work for the elimination of nuclear weapons. Another reason has to do with a sense of the sacredness of creation and a belief that we do not have the right to place it at such hazard. That is really a matter of the heart.

In 1971, I met the most humble and dedicated human being one can become and I studied with him until his passing in 1986. A small elderly sage found in the jungles of Sri Lanka, known to the world as Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, thought of as a swami or guru by his Hindu disciples and a Sufi sheikh by his Muslim devotees, he lived with the complete fullness of love demonstrating in his daily life of service several insights. First, if one wants to achieve true peace they must desire for others the peace they want for themselves. Second, they must serve to help others obtain that peace. Third, they must separate from themselves that which separates them from others. He taught me that when there is justice the presence of God can be known and that nonviolence and reverence for life awaken, enhance, and amplify wisdom. By his living example, he showed me that the teaching of all the great religions, all the traditions of wisdom, an d the intuitive reasoning of conscience can be honored by bringing compassion into action.

Senator Alan Cranston helped me learn that living such an exalted teaching is not only internally fulfilling but manifestly effective and practical. Senator Cranston was my political mentor and founder of the Global Security Institute, where I presently serve as President. After meeting Albert Einstein in 1948, he concluded that nuclear weapons are unworthy of civilization. He taught me that the world of politics can be informed by the most basic moral values inherent in all law and justice – treat others as one wants to be treated. This principle of equity is the basis of stability. When it is violated instability ensues. When pursued, especially when backed by law, justice arises.

A system where a handful of states claim that they have a unique right to possess and threaten to use weapons of mass destruction while telling others that t hey would be evil if they pursued the same course is both impractical and unstable. Moreover, it flaunts the legal obligations contained in the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and the unanimous ruling of the International Court of Justice, which stated in 1996: “There exists an obligation to pursue in good faith and bring to a conclusion negotiations leading to nuclear disarmament in all its aspects under strict and effective international control.”

Judge Christopher Weeramantry, sitting as Vice President of the International Court of Justice, said: “Equality of all those who are subject to a legal system is central to its integrity and legitimacy. So it is with the body of principles constituting the corpus of international law. Least of all can there be one law for the powerful and another law for the rest. No domestic system would accept such a principle, nor can any international system which is premised on a concept of equality.”

Senator Cranston persuade d me to utilize the gifts of legal training to become a public advocate for advancing the rule of law and equity in international relations. He understood that without the elimination of nuclear weapons, global stability will evade us and that the path to nuclear weapons abolition would itself enhance the highest public good, peace and security.

My dearest friend Canadian Senator and diplomat, Douglas Roche, has taught many of us to see and state clearly the underlying moral foundation of political analysis. Here is an example of this powerful approach.

Imagine if the Biological Weapons Convention said that polio and small pox are prohibited for all countries, except for ten countries which are so upright and responsible that they can spend trillions of dollars to develop and use the plague as a weapon to help maintain global security. Biological and chemical weapons are banned for all, but ten countries claim a right to threaten to use nuclear weapons. In addition to the moral incoherence of this position, its inequity leads to instability and when dealing with weapons of such destructive magnitude this is impractical and immoral. It is time to advance a legal norm that will make us all safer — walk down the nuclear weapons ladder, obtain a test ban, a prohibition on the production of fissile materials, to strengthen verification and monitoring, and sooner rather than before its too late, negotiate a non-discriminatory, legally verifiable, universally enforceable nuclear weapons convention, prohibiting the possession, production, use and threat of use of nuclear weapons entirely.

These great teachers guide us to bring justice into an international legal order and beautiful qualities into our personal lives. And each of these teachers in turn has honored deeply those who went before them. Senator Cranston kept a quote from Lao Tzu in his wallet to remind him each day of how leadership should best be exercised. It is relevant because amongst us here today are several dynamic, effective, passionate leaders as well as youth who will lead tomorrow.

A leader is best

When people barely know

That he exists,

Less good when

They obey and acclaim him,

Worse when

They fear and despise him.

Fail to honor people

And they fail to honor you.

But of a good leader,

When his work is done,

His aim fulfilled,

they will all say,

‘We did this ourselves.’

Thank you so very deeply for allowing me to share these words with you.

![]()