Special UN Panel Event Report

By Jesse Zeigler

|

|

|

Dr. Jeffrey Sachs and Dr. Jane Goodall

|

|

On May 10, 2010, the Global Security Institute, with co-sponsorship by the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, convened a panel of distinguished thinkers and activists at United Nations Headquarters to discuss the severity of humanity’s recent impact on our habitat through the converging threats of commercialism, ravenous consumption, and archaic attitudes toward nuclear weapons.

At the helm of this discussion was GSI President Jonathan Granoff, joined by Dr. Jane Goodall, UN Messenger of Peace and founder of the Jane Goodall Institute, Dr. Jeffrey Sachs, Director of the Earth Institute and Senior Adviser to former Secretary-General Kofi Annan, and Ambassador Thomas Stelzer, the UN Assistant Secretary-General for Policy Coordination and Inter-Agency Affairs. Mr. Stelzer’s career has taken him to the forefront of the disarmament movement as Austria’s Permanent Representative to the International Atomic Energy Agency and as Special Assistant to the Executive-Secretary of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty Preparatory Commission.

The two-hour-long panel focused primarily on fostering connections between the critical goals of global disarmament and committed sustainable development for all living beings on the planet. Those in attendance included delegates to the 2010 Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) Review Conference as well as voting members and observers to the Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD-18).

|

|

|

Jonathan Granoff

|

Mr. Granoff opened the discussion by quoting President Oscar Arias of Costa Rica, who told the Security Council last September that “22,000 eyes of death are looking at us every night when we go to sleep.” He continued by stating that tonight, mothers around the world will decide how many calories they can dole out to their children and that the pH of the oceans will continue to slide off balance. He spoke of the perils we face as our moderate climate recedes into memory, and the more than “100 species which will be ripped from the pages of the majestic, sacred scripture of the book of life.” The resolution of these crises, he argued, requires global cooperation.

He then framed the discussion in the form of three questions to our political leaders, and invited the panel to answer them in a substantive fashion:

- What are your plans to discuss crushing poverty?

- What are your plans to protect the environment?

- What are your plans to eliminate nuclear weapons?

Dr. Sachs began the discussion by stating the sweeping role of cooperation necessary to address these problems on multiple fronts, placing emphasis on the diplomatic difficulties that confront progress on these issues. He summarized the responsibility of mankind to future generations by stating, “ The underlying paradox of our age was expressed 50 years ago by (President Kennedy) in his inaugural address—man holds in his hands the power to abolish all forms of human poverty and all forms of human life. We invent to create and we invent with the capacity to destroy. We haven’t settled the question of which path to take. Which will it be? This is the essential paradox of our times.”

|

|

|

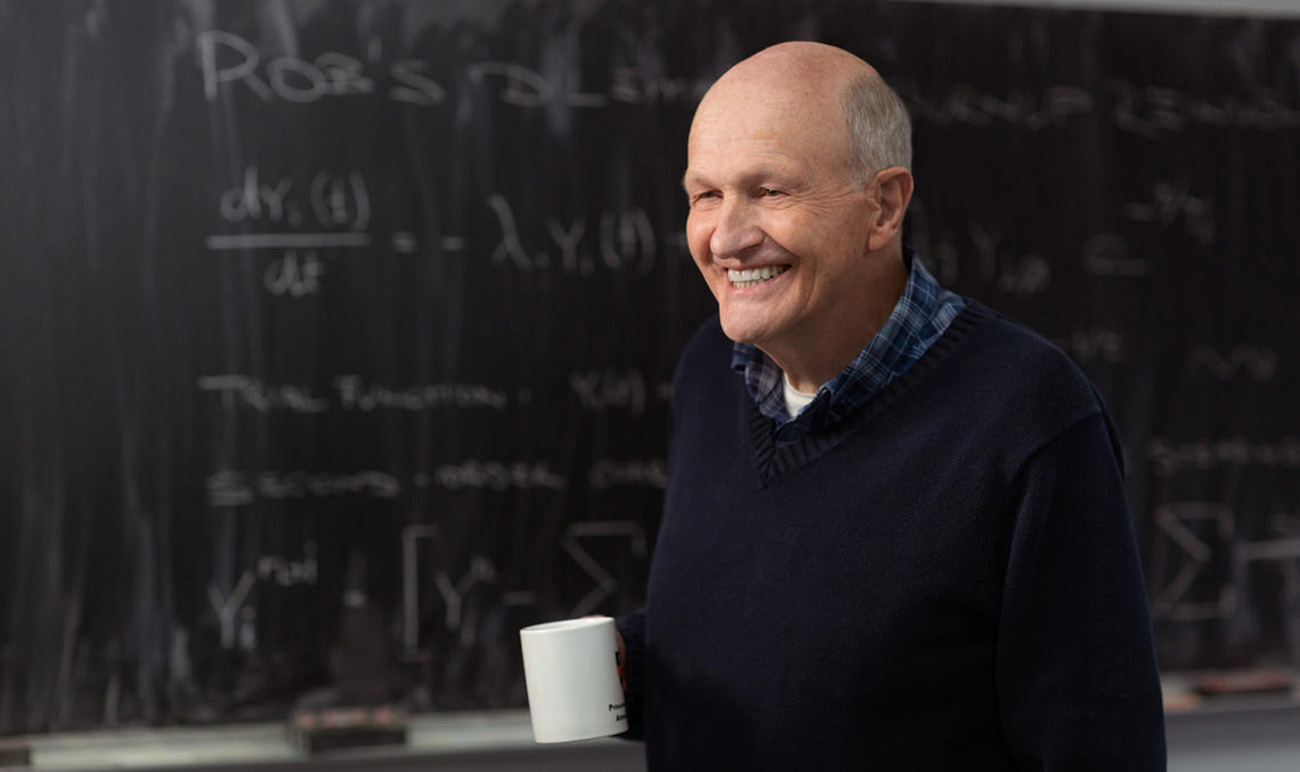

Dr. Jeffrey Sachs

|

|

It is Dr. Sachs’ belief that the intrinsically intertwined nature of these issues is the greatest obstacle we face in trying to address them. We know that we cannot achieve success one issue at a time, but can instead only do so with each part acting in concert. As we build toward war, our greatest mistake as a species is that we neglect to build for peace through the elimination of global poverty. He said that the US government will spend more than $750 billion on the military approach to our world and less than $30 billion on the peaceful development of assistance; for example, the United States will spend $1 million per soldier this year in Afghanistan, and the amount spent on each could instead rescue an entire village somewhere in the world.

“Whenever I petition my government to build a school or dig a well in a peaceful area of Afghanistan, the response I get is that there is no money for that since those dollars must be focused on the war zone. Well, if that’s the attitude we adopt, then all we will have in this world are war zones, ladies and gentlemen,” Dr. Sachs said.

Changing the way we approach conflict is crucial to addressing sustainable development and continued human stewardship of the planet. Dr. Sachs then followed by declaring the issue of civilized migration being integral to the ramifications we face: “When people move out of desperation, they get shot upon arrival in many parts of the world where conflicts erupt.” He believes that these local failures are becoming global failures since we are increasingly interconnected and interdependent.

Dr. Sachs closed his remarks with an excerpt from President Kennedy’s peace speech, aiming it at pundits who feel that it is better to knock down discussion than build toward results. He began by saying that we must first examine peace itself.

“Too many of us think it is impossible, too many think it is unreal, but that is a dangerous, defeatist belief. It leads to the conclusion that war is inevitable. That mankind is doomed. That it is gripped by forces we cannot control. We need not accept that view. Our problems are manmade; therefore, they can be solved by man. And man can be as big as he wants. No problem of human destiny is beyond human beings. Man’s reason and spirit have often solved the seemingly unsolvable, and we believe they can do it again. I am not referring to the absolute infinite concept of universal peace and good will of which some fantasies and fanatics dream. I do not deny the value of hopes and dreams, but we merely invite discouragement and incredulity, making that our only and immediate goal. That we instead focus on a more practical and attainable peace, based not on a sudden revolution in human nature but a gradual evolution in human institutions. On a series of concrete actions and effective agreements which are in the interest of all concerned. There is no single, simple key to this peace. No grand or magic formula to be adopted by one or two powers. Genuine peace must be the product of many nations, the sum of many acts. It must be dynamic, not static, changing to meet the challenge of each new generation. For peace is a process, a way of solving problems.”

Dr. Jane Goodall began her talk by discussing the biological and behavioral similarities we, as humans, share with the wider global community of chimpanzees. Our brains only differ in size, she said. They share much with us, including a capacity for violence and brutality, and suffer from the same territorial distinctions and exclusionary attitudes that blight humanity today, ones that can only be solved by a wider, collective effort transcending the pitfalls of nationalism, race, ethnicity, and creed.

Dr. Goodall related the professional difficulties she confronted when she first began to describe what she calls the “Four-Year War,” an incident in which one group of chimpanzees annihilated another, saving only the females. Many of her colleges suggested she censor her findings, which they argued would lead some to believe that violence and war were inevitable in the human species. She countered this argument with evidence that human beings have also nurtured such capacities as love, compassion, and altruism, and she then stressed our intellectual capacity to communicate our plans for the future and comprehend our past. Foresight is the thing that can set us apart from the violence we have evolved from, she said. We can create a moral sense unlike other forms of life on this planet, which endows us with a greater responsibility to ourselves and to those with whom we share “poor, old, battered Mother Earth”.

In closing, she stated, “ Underneath the color of skin and the dressing beats the same human heart and the same need for love and the same kind of emotions. This is the message: a way forward, a way of hope, out of the mess that we have made.”

To the UN official charged with policy coordination and interagency affairs, Ambassador Stelzer is keenly aware of the linkages between development, planetary sustainability and global security. “I was struck two years ago,” he opened, “when Admiral Dennis Blair, the Director of US National Intelligence, in a meeting with the United States Senate, was asked what, in his perception, are the biggest security threats to the US—and he didn’t say it was terrorism [and the nuclear threat], but eroding national structures in the face of successive crises. He said this in May 2008, right after the food crisis of March 2008,” he stated.

|

|

|

Assistant Secretary-General Thomas Stelzer

|

Amb. Stelzer added that the food crisis was preceded by a market crisis and has resulted in the current employment crisis, and that these occurrences are systemically linked to global security—which furthers Dr. Sachs and Dr. Goodall’s requirement of integrated cooperation in finding concurring solutions involving both state and non-state actors. To clarify his statement, he outlined six clusters of threats and their relation to the questions posed by the chair, Mr. Granoff.

Mr. Stelzer gave a thoughtful analysis of current global trends regarding climate change and stressed that the recent talks in Copenhagen demonstrated that this issue has taken center stage to many prominent and influential leaders: “45,000 people lined up for passes to the discussion, some [waiting] as long as 12 hours during snowstorms which happened every day of the summit. 150 world leaders came to Copenhagen, perfectly aware that they are facing an issue that might not render any results yet, but the issue was important enough to their constituents to have them come and try their best.”

Climate change, he said, is very often referred to as a threat multiplier that works through several channels to exacerbate conflict and insecurity. It is in our hands to take up the political effort to control and minimize this threat, he said. “It took us a long time to realize that the United Nations was not just a forum for governments to communicate but, as is stated in the Charters Preamble, is here for the peoples of these nations to communicate. “The United Nations was not formed to create paradise on Earth, but to save us from Hell.” he said.

Member states, civil society, and academia should all have a sense of ownership of this institution in order to succeed in a place like Copenhagen. This is the Secretary-General’s stated strategy in order to move toward a cooperative and coordinated body. The ambassador also stated that development and security are becoming increasingly one and the same to members of the Security Council: “What are people doing who are starving? They either rise up, they migrate, or they die. These are the three options, and each of them has enormous security implications—which is why it is so very important that we have you all [civil society and academia] here today.”

GSI President Jonathan Granoff spoke last, drawing three principles together for the delegation and pointing to the wider focus that humankind must adopt if we are to survive ourselves.

The first principle stated that we must affirm that we are one human family—that this is a reality now. Instead of moral and spiritual insight, we must regard it as practical insight. As Saadi, the Persian poet of the 13 th Century once said, “The human family is one body with many parts; creations are rising from unseen essence, ” Mr. Granoff asserted that we need global cooperation and global norms to protect the climate and address poverty and weapons of mass destruction; if any state has them, he maintained, others will want them and get them, and, if they exist, they will eventually be used.

The second principle is one of the oldest: the Golden Rule, or treat others as you want to be treated. “This is a rule that has to be applied now, between states. This principle of mutual understanding is important—if your country behaves, as a powerful country, others will follow. Every country must ask: Is our country and way of life sustainable?”

The third principle, and quite possibly the most important, is about the reverence for life: “We cannot view success as just security of the state, but the security of the living systems and the people within them,” Mr. Granoff said.

The session closed with a brief question and answer period where delegates raised issues to the panel regarding the militarization of weather science and the stress of unchecked population growth on the allocation of global resources.

In a powerful last intervention from the floor, a young delegate from Germany thanked the panel for their inspirational words, especially Dr. Goodall and Mr. Granoff for their tireless efforts to energize and educate youth movements around the world; “Just now listening to your talks I think there is an incredible opportunity for convergence, not just of issues, but of young people whose hearts are beating very strongly on these specific issues of development and global justice. I myself am rather committed to the issue of nuclear disarmament, so please Ms. Goodall, please Jonathan, lets continue to work on this and really have a convergence of youth groups so that together we can form a global movement that is even more powerful, working for a world that is more just, sustainable and free of the threat of nuclear weapons.”

![]()

Jonathan Granoff is the President of the Global Security Institute, a representative to United Nations of the World Summits of Nobel Peace Laureates, a former Adjunct Professor of International Law at Widener University School of Law, and Senior Advisor to the Committee on National Security American Bar Association International Law Section.