March 31, 2008

Will evangelicals show the will to pursue the prevention of a pending threat?

by Tyler Wigg Stevenson

Originally published by Christianity Today

At 10:13 a.m. on Thursday, May 25, 2017, a 14-foot U-Haul truck will abruptly come to an inexplicable stop in the middle of the 900 block of Pennsylvania Avenue. There, in the heart of downtown Washington, D.C., only yards away from the FBI and the Justice Department, the nuclear warhead hidden in the truck’s cargo bed will explode.

The weapon will be the same gun-type design as the Hiroshima bomb, crude and weak and inefficient by modern standards. But at 15 kilotons, the blast radius will cover 1.5 miles, encompassing and destroying the White House, the Capitol Building and Congressional offices, and the Supreme Court; the buildings housing the IRS and the Departments of Energy, Commerce, and Transportation; and the Washington Monument, the Smithsonian, and the National Mall and Museums.

That morning the district will be bustling with workers clearing their inboxes prior to the long Memorial Day weekend and tourists who are already making the rounds. Tens of thousands of people will die in the first minutes. The dead include the majority of all nationally elected officials, including the President and Vice-President, as well as the core employees in each branch of the government.

Additional tens of thousands will die both quickly and slowly by asphyxiation, burning, and building collapse in the subsequent firestorms. And the number of critically injured will dwarf the number of initial fatalities as the regional health-care system collapses. The ledger of the dead will overflow as radiation and the plume of deadly smoke take their toll on downwind communities, whether Baltimore or Arlington.

Now, the stunned silence. Now, the widespread panic. Now, the disaster response.

Now, the howls for retribution.

Now: What does the American church do?

One thing the American church will almost certainly do in such a situation is wish that it had done something sooner.

Broad Is the Way That Leads to Destruction

The above sounds like the plot of a movie, too horrifying to be real. On the other hand, that’s just how the prospect of knife-wielding terrorists using passenger planes as guided missiles would have sounded to most of us on September 10, 2001.

Professor Graham Allison, director of the Belfer Center at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, gives worse than 50-50 odds to the possibility of our going 10 years without a nuclear terrorist attack, which he calls “the ultimate preventable catastrophe.” (It gets worse: He started counting in 2004.) And the famously understated Warren Buffett, who made his billions in part by insuring insurance companies, says of a nuclear attack on the U.S., “it’s inevitable.” Buffett observes that if there is a 10 percent likelihood of a nuclear attack each year, our 50-year likelihood of seeing a disaster like that described is 99.5 percent.

In other words, unless we’re able to prevent such a scenario, it’s something we need to try to be ready for — even if we never face the governmental decapitation from an attack on Washington, D.C., but still incur the comparable human loss from the destruction of any other city: Pittsburgh or Dallas or Los Angeles.

At present, we’re whistling down the road to disaster, maintaining a nuclear status quo that will be our undoing. But it doesn’t have to be this way. The future can still be changed.

Not Your Daddy’s Disarmament

“We are at a tipping point,” says George Shultz, President Reagan’s Secretary of State and an architect of the end of the Cold War. “The simple continuation of present practice with regard to nuclear weapons is leading in the wrong direction. We need to change that direction. We cannot wait for a nuclear Pearl Harbor or 9/11.”

He adds, “If we wait — if a nuclear accident occurs — the world will be changed so dramatically that we will not recognize it. So wake up, everybody.”

This conviction led Shultz on January 4, 2007, and again on January 15, 2008, to join fellow Republican Henry Kissinger and two hawkish Democrats, William Perry and Sam Nunn, in authoring Wall Street Journal op-eds calling for complete nuclear disarmament. Their rationale is simple: A nuclear arsenal, regardless of size, cannot deter a terrorist bomb with no return address. And the continued insistence of the nuclear weapons powers that such weapons are indispensable for their own security is the single greatest stimulus to other nations wanting to acquire them.

In other words, the United States presently faces a rapidly-closing window of opportunity — the “tipping point” referred to by Shultz, above. We can either doggedly cling to our own arsenal, ensuring that such weapons will eventually be used against us, or lead an international process toward a world with zero nuclear weapons.

If this world sounds like a hippie, leftist fantasy, consider that a non partisan supermajority of the former secretaries of state, defense, and national security advisers have endorsed the vision and a process to get there — including Colin Powell, Jim Baker, Frank Carlucci, and Melvin Laird, as well as a dozen additional top foreign-policy officials from the Reagan administration. And newly declassified documents offer overwhelming historical evidence that Ronald Reagan was a fervent — and utterly misunderstood — abolitionist.

The cause catalyzed and now led by the WSJ co-authors — being conducted soberly by men and women in dark suits, at venues like the notoriously conservative Hoover Institution — couldn’t be further removed from marchers wielding “no nukes” signs.

And conservative evangelicals, who have been historically leery of the liberal peace movement, are finding a place in this burgeoning coalition. The Biblical Security Covenant, which works with Shultz and affiliated efforts, is marshaling a theologically orthodox evangelical commitment to work for a world beyond nuclear weapons.

We’re not talking about unilateral disarmament; no, the proposals currently underway describe an international framework that would combine prohibition and verifiable elimination, along with a mechanism to prevent nuclear breakout by potential cheaters.

But neither are we talking about a pie-in-the-sky “someday” goal that can be supplanted by a mere laundry list of policy goals. The vision of a world without nuclear weapons gives urgency and moral nobility to the political process needed to get to zero.

Who Hopes for What They Already Have?

Nuclear weapons can seem so faceless, so distant, that ordinary people feel paralyzed to act on their convictions. But the good news is that right now, in 2008, we face a once-in-a-generation opportunity, like the one that slipped through our fingers at the Cold War’s end. In the past couple of months, Congress has mandated two blue-ribbon commissions to investigate our national nuclear-weapons policies. The first, appointed by Congress, will report this December. The second will be conducted by the next White House and report in early 2010.

This means we’re on the cusp of a national conversation about what kind of world we want to live in. And everything could change if the American President embraced this vision and made zero nuclear weapons worldwide a personal and administration priority.

So there’s a task confronting us, those called by God to be disciples of the Lord Jesus Christ while citizens of the United States: When the next President takes the pulse of public will on this issue, what will our national evangelical witness look like?

The present champions of a nuclear weapons-free world are not naïve — on the contrary, many of them witnessed firsthand the worst evils of the last century in the same global conflagration that birthed the bomb. Nevertheless, they hope; in hoping, strive; in striving, exemplify courage.

The youth that fought WWII are now grown old, and will not likely live to see the world for which they now labor. Their example of enduring hope speaks well to why Christians can and should take our stand for a world beyond nuclear weapons. It is not because we seeds of resurrection are panicked by mortality, nor because we citizens of the kingdom are driven by national interest over righteousness, nor because we imagine that we can add an ounce of worth to the redemption performed on the Cross.

No: It is because we are experts at God-given rejoicing in the present for a world that has not yet arrived. So we are driven now by the future day when we wake to headlines that the last bomb has been consigned to history books and museum displays. We’re no strangers to such preemptive joy, after all: it’s the very thing that has fueled the church’s testimony to life throughout history’s death-filled days, and to a love that casts out fear — in this and every terrorizing time.

The Rev. Tyler Wigg Stevenson, a Baptist preacher, is director of the Biblical Security Covenant.

![]()

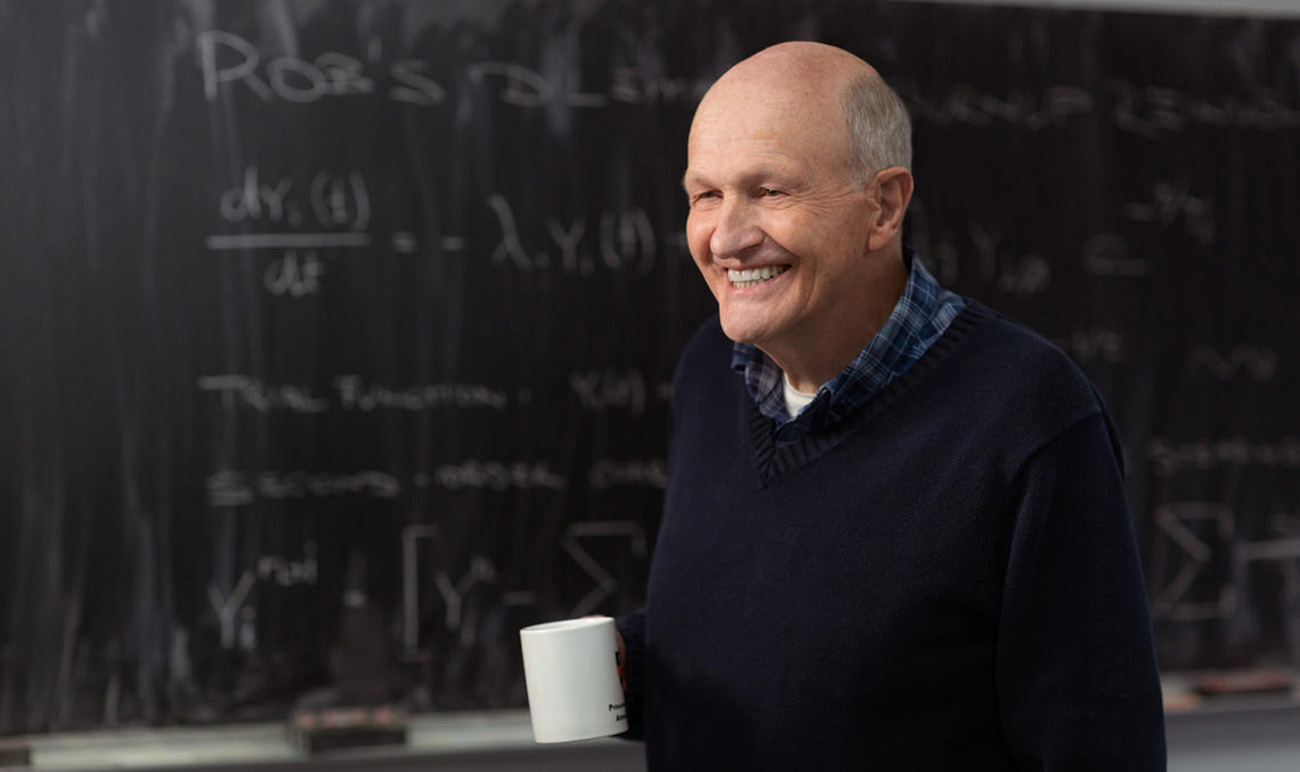

Jonathan Granoff is the President of the Global Security Institute, a representative to United Nations of the World Summits of Nobel Peace Laureates, a former Adjunct Professor of International Law at Widener University School of Law, and Senior Advisor to the Committee on National Security American Bar Association International Law Section.