By Tracy Early

Tidings Online

Friday, June 3, 2005

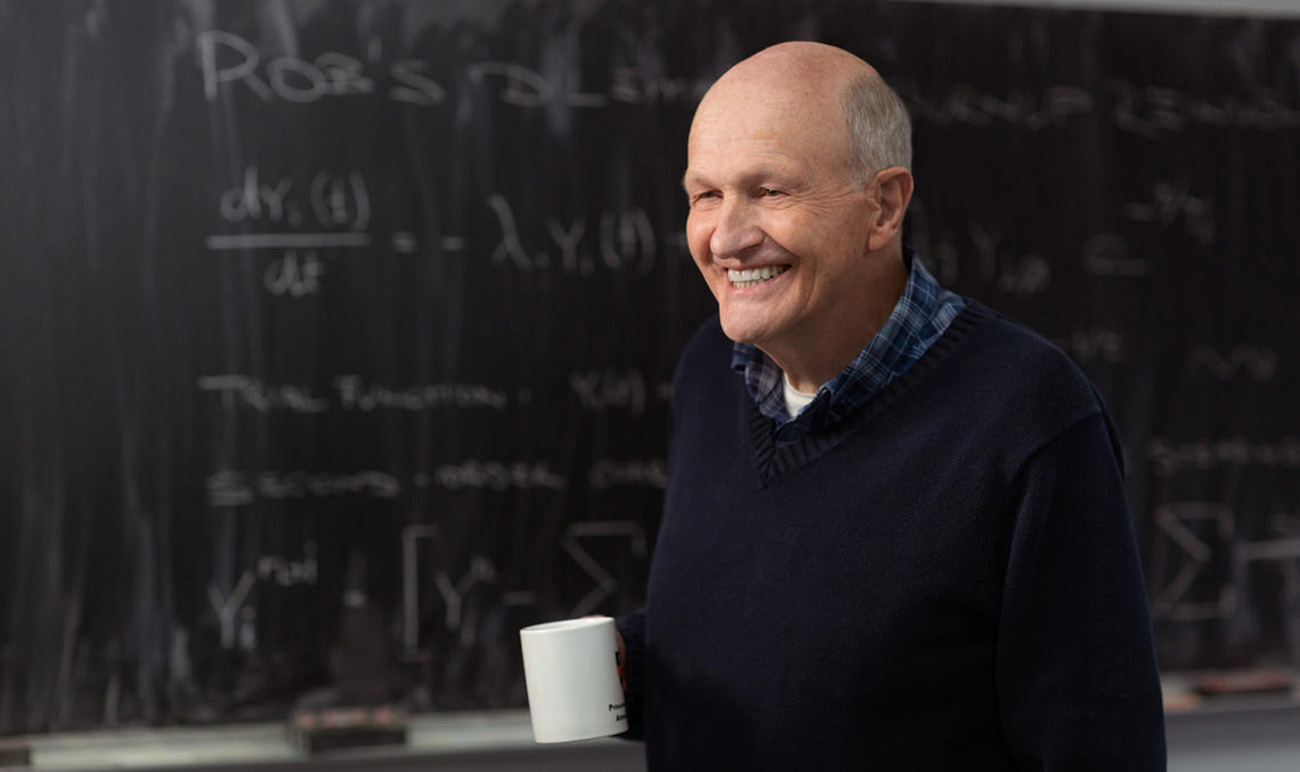

The religions of the world “need to speak up much more strongly” about nuclear disarmament, a Canadian adviser to the Vatican on disarmament and security issues told a United Nations meeting last week.

Calling nuclear weaponry “the paramount moral issue of our time,” Douglas Roche, a Canadian adviser to the Vatican on disarmament and security issues, said May 27 said that “nuclear weapons and human security cannot coexist.”

Roche said, however, that the world’s religions alone cannot exert sufficient influence to move the nuclear powers to disarm and would have to work in alliance with other concerned members of society. Contemporary society is largely secular, and even a “sustained high-level joint religious call” would not be sufficient to make it respond, he said.

But he said the religious community could find ways of aligning itself with the “secular humanistic culture” to speak about “values that are human – for people of faith and people of no faith.”

Roche, a former member of the Canadian Parliament and former diplomat, served on the Vatican delegation to a conference held at U.N. headquarters in New York May 2-27 to review compliance with the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

According to news reports, the conference came to an impasse mainly because the United States and a few other countries, seeking to put pressure on North Korea and Iran, were at odds with the many countries that wanted to get the United States and other traditional nuclear powers to move faster toward nuclear disarmament.

On the final day of the conference, Roche participated in a panel discussion at the Church Center for the United Nations, across the avenue from U.N. headquarters. The event was sponsored by the Fellowship of Reconciliation, Pax Christi USA and the interreligious agency Temple of Understanding.

Roche reported that in a statement to the review conference Archbishop Celestino Migliore, the Vatican’s U.N. nuncio, took a “strong stand” that “has been noticed.”

During the Cold War, Roche said, the Vatican expressed a limited acceptance of nuclear deterrence, but only as a step toward total nuclear disarmament.

After the Cold War, however, the nuclear powers indicated they planned to make their nuclear weapons permanent, and the Vatican has now “withdrawn any acceptance of nuclear deterrence,” he said.

Arguing that religious leaders do not recognize the gravity of the nuclear issue, Roche said they needed to help their people understand the “doublespeak” that governments were using to justify the possession of such weapons.

Even a low-yield nuclear weapon would endanger life on earth, and constitute an assault on the planet as a whole, he said.

Dave Robinson, executive director of Pax Christi USA and also a panelist, called the U.N. review conference “frustrating and pointless” because “officialdom did not come up with anything.”

He said, however, that encouragement came from the great increase since the 1995 review conference in the number of nongovernmental agencies that brought representatives to the United Nations to observe and lobby.

He welcomed the Vatican statement and said it will be helpful in persuading American Catholics to support nuclear disarmament.

A press release issued by the United Nations on the last day of the review conference said several of the official delegations were “expressing deep disappointment at the outcome,” particularly the inability to develop enough consensus to produce a final document.

Norway’s representative said “the international community had been unable to address issues like noncompliance, defection from the treaty and terrorists’ desire to obtain mass destruction weapons.” North Korea has withdrawn from the treaty, and the “defection” reference was apparently an allusion to that country’s action.

Chile’s representative said the conference “could only be described as a failure.”

At the panel across the avenue, Dominican Sister Eileen Gannon, moderator, echoed that judgment, declaring that the four-week event then in its final day was “not a successful conference.”

It is “hard to be hopeful,” she said.

Another panelist, Ibrahim Ramey, coordinator of the disarmament program of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, said the conference was “not a reflection of the best human possibilities.”

Among those listening to the panelists were a number of young people, including several who had come from the University of St. Thomas in Miami to see the United Nations in operation.